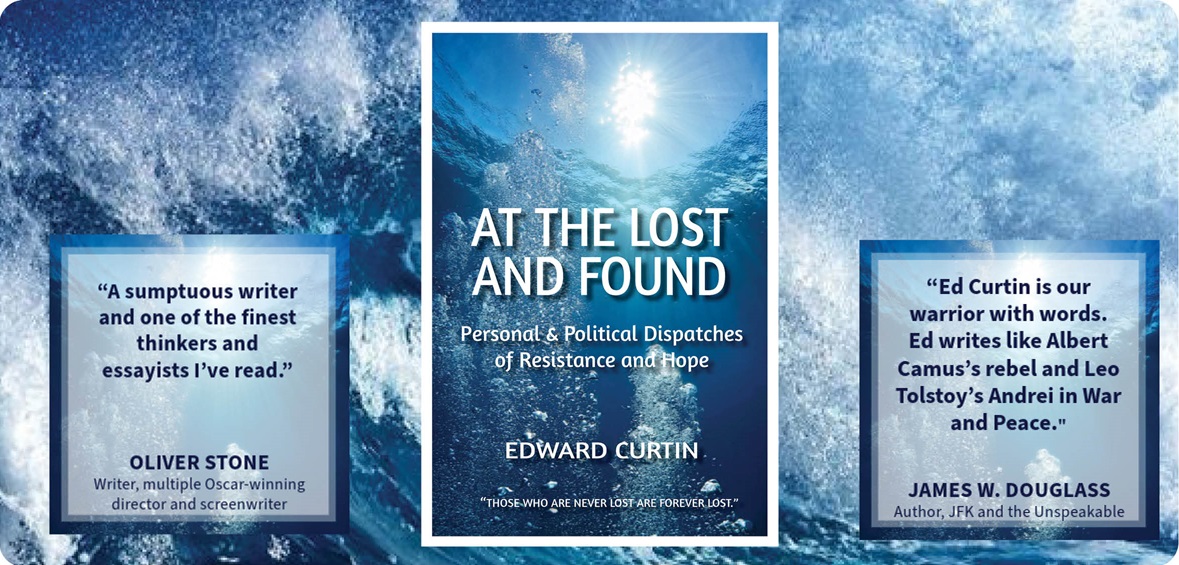

The following is the Introduction to my new book, At the Lost and Found (Clarity Press).

My dear mother, who had an artistic temperament that tended at times toward the sentimental, liked to call me a contrarian. She was right. I think she liked but feared this inclination of mine that started in childhood. It no doubt has many roots, some of which an artful reader may sense in the essays in this book, for while I have written about the lies and coverups of the ruling elites, I have tried to do so in a self-revelatory way, even in the writing where it is couched in pure artifice.

I have always felt that conventional life was a provocation because it hid more than it revealed; that it harbored secrets that could not be exposed or else the make-believe nature of normal life would collapse like a cardboard set. That people were performing for some invisible director that they couldn’t or wouldn’t recognize. I always wondered why.

There is nothing profound in this tendency of mine, except the powerful force of it throughout my life. Like everyone, I was ushered onto this Shakespearean stage and have acted out many roles assigned to me but always with the inner consciousness that something was amiss. Everyone seemed to be playing someone, but who was the player? Who was I?

Because I grew up in a large literate family where our sizable bookcase was filled with great literary classics, I have always loved to read. I noticed early on that the great writers focused on this performative nature of social life, and this strengthened my burgeoning artist’s eye. I particularly remember the family set of Mark Twain’s books that drew me in this direction, his humorous ways of puncturing social hypocrisy.

My writing was born within all my reading, including my grandparents’ large and colorfully illustrated volume of Arabian Nights that I would sneak a peek at from time to time. Then there was my father’s witty storytelling where he would regale me with his improvised tales drawn from the metaphoric well of Pinocchio’s theatrically duplicitous adventures.

By the time I was a young man, my mind was a vast store-house of words, phrases, metaphors, tunes, memorized lines of poetry, etc. that sometime I could consciously recall but that often would just pop up like jack-in-the boxes to startle and amuse me. This has continued throughout my life – even as I never tried to remember it all and even tried to forget much of it. My forgettery has always been my faithful servant.

I am telling you this for a few reasons. One is that I have noticed that many writers seem afraid to reveal who they are or what motivates them to write. They hide the personal side behind a false objectivity. This is especially true for writers whose focus is political and involves public and cultural affairs, as does much of mine.

I think of Thoreau’s words: “We commonly do not remember that it is, after all, always the first person that is speaking.”

And that person, with all their hopes, dreams, desires, politics, ambitions, personal relationships, predilections, habits, faith, despair, etc., informs their work, no matter how seemingly authoritative and objective it may sound. What that person wants from writing or any art is a fair question, just as it is the core existential question for everyone: What do you want and why? What are you seeking by doing what you are doing? What is your goal?

Readers want and need to know something (not everything) about the person whose hand pens the words they are reading. It is a normal human response to ask, “Well, where is this person coming from; what’s in it for him?”

It is banal to say that one has learned so much from so many others, but it’s very true in my case. Not just the living but all those who have preceded me and whose words and creativity have become part of who I am, my memories, all that I have read, heard, seen, and forgotten but emerges when I write, in ways I realize or not.

It is mysterious; it happens through osmosis, but in the end one hopes the result is creative and new and that the writing is a place of epiphanies.

I admit that I am possessed by language and that it precedes the content of what I write. Maybe words possess me. I don’t know, nor do I care. I just know it’s so. So the mélange of the wide-ranging and free-wheeling essays that result, their multifarious styles and content, fits with my contrarian personality that seeks to do both astute political analyses and art in luminescent words and sentences that pulsate. I think of them as beyond a cage of categories and intertwined lovers.

I wrote the essays in this book between late summer 2019 and 2024. The topicality of many will be apparent, but I hope you will find in them more than contemporary relevance. I hope you will find me, Ed Curtin, one man who lived through these strange and disturbing years and responded in his own way. One man whose core concerns are essentially no different from the serious contrarian poets, writers, journalists, philosophers, musicians, painters, and artists throughout world history.

There are those who are trying to mechanize us all, to eliminate passion and will, to transmute love into a chemical and hate into a biological aberration. They seem to be succeeding, but they will fail. One reason I have written these essays is to oppose these scoundrels and their ilk who kill and wage endless wars against innocents around the world. Another is to try to create something that will delight and last a little while. I believe that writing is my vocation and that I am answering a call, and if there is any credit due, it is beyond me.

It is a very cruel world, as events over these last few years have confirmed. It is hard to wake up in the morning and hear the news. It leaves one with a sense of lostness that must be fought. The spirit of resistance can be found in many places, including poetry and song. I often remember the words of a poet that my mother had memorized and liked to recite, William Wordsworth, whose romanticism flows in my veins as well. He ended his great poem “Intimations of Immortality” thus: “Thanks to the human heart by which we live,/Thanks to its tenderness, its joys, and fears,/To me the meanest flower that blows can give/Thoughts that do often lie too deep for tears.”

Nietzsche was right about writers when he said their work is a personal confession, “a kind of involuntary and unconscious memoir.” No doubt this is true for me.

Finally, I hope that in reading this book you will find the words of Yuri Zhivago in the novel of death and resurrection, Doctor Zhivago, by the great Russian poet and novelist, Boris Pasternak, echoing in your mind. As he contemplates being possessed by the mystery of inspiration while writing poems, Yuri writes this: “Language, the home and dwelling of beauty and meaning, itself begins to think audible sounds but by virtue of the power and momentum of its inward flow.”

Since Zhivago means “living” in Russian, it is my wish that these essays live in your memory like the sound of music deeply felt, the same inward flow I felt when writing them.

Is a child’s first question, unspoken, when entering the world from leaving the womb, ‘what is this and who am I ?’

Afraid to reveal who they really are, through their writing? Yes and with good reason don’t you think? To reveal makes you vulnerable, it took me decades to even air the thoughts that have haunted me throughout my life and it was fear that held me in its grip. Fear of exposure, of ridicule. It’s only now, in the 80th year of my life that I can contemplate revealing such thoughts, perhaps because I no longer the fear that the words will hurt me?

Or that the words can no longer hurt the living?

“I admit that I am possessed by language and that it proceeds the content of what I write.”

Proceeds or precedes?

Thanks, it should be precedes and it’s changed. You are very helpful.

Marcus Aurelius began his ‘Meditations’ by acknowledging those he had learned from, and what he’d learned from them. Thanks for your writing, Ed.