Although my father, whose namesake I am, died twenty-nine years ago, I just spent a hilarious and profound afternoon with him. For a few hours on a beautiful late spring afternoon, I sat out on the porch and listened to his inimitable voice beguile, instruct, and entertain me. He had me laughing out loud as I read through a large folder of letters he had sent me over the years. We were together again. It was his voice I heard, his voice speaking to me. It could be no other. In the beginning and end are the words. If we are lucky, we hear them.

It’s sad to think that the era of letter writing may have ended and future generations left bereft of this deepest of consolations. Emails in a cloud won’t do; they lack the soulfulness of the human hand. They delete the person.

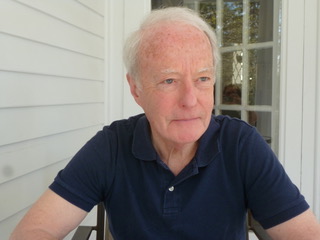

My parents had nine children and raised us in the Bronx. I am the only son. My father and I were very close. I talk to him daily, but it is only with the approach of Father’s Day that I reread his letters in an effort to honor him, to remember him. It is usually then that I hear him respond. One look at his handwriting – so unusual – and he is present.

And then the voice.

“The other day Mama saw a death notice of an Edward J. Curtin but happily he came from Brooklyn so it wasn’t either of us. I told you things would get better.”

“I am up at this ungodly hour (3:35 AM) because I just had sort of a nightmare in which I was an official hangman with the unpleasant task of hanging Mrs. Grossman, one of our neighbors whom I rather like – very unpleasant stuff these dreams are made of. I don’t think I’ll delve into this one with my guru or analyst.”

Back from a doctor’s visit, he reports: “The doctor said I have only two problems – from the waist down and from the waist up. But from the neck up I think I’m okay. Cogito ergo sum.”

On my mother trying to buy him pants: “Seems that my waist is too big and my ass too small. I think I’ll get a tummy tuck.”

As a lawyer, he was regularly in court and would pen these epistles, as he called letters, while he was waiting for court to begin. “I’m sitting in the bullpen waiting for my case to be called. Today’s case involves a group of fun-loving youths who, at a certain midnight, took a watch from a woman at gunpoint. My client, of course, was just asking her for the time because his mother told him to be home by 3 AM.”

Sardonic, yes, but with a great human touch and a sense of care and empathy unmatched. “On Tuesday while waiting at the court a young black woman sat down beside me and said, ‘You’re my uncle, you’re my great youngest uncle. I have five sisters and six brothers – all no good.’ I think she also said I was handsome and, after admiring my ‘baldy’ haircut, she kissed me on the cheek. Later, I was in court when she was remanded to Jacobi Hospital for observation. Very sad.” He later visited her in the hospital.

That’s my father, a wonderful father, and not just to me or my sisters. He had a way with people that invited them to confide and trust him.

His letters are not just jocular riffs that get me howling. There were many difficulties and tough issues to contend with. And his letters are filled with them too. They are like mini-short stories, akin to a father sitting beside a child’s bed and telling him a goodnight tale. They always end on an up-note, no matter how serious what precedes. He was a storyteller talking to an adult son, just as in my childhood he would tell me bed-time improvisations on the Pinocchio story, tales of lies and deceptions and bad actors. Those stories had to have an edge to them, a bit of a question mark, just as his letters are peppered with the phrase quien sabe (who knows?) He knew and he didn’t know; had strong opinions, but he knew when it came to the human heart, he didn’t know it all. He respected the mystery and therefore had great empathy for individuals he encountered, and they sensed that in him.

But there were exceptions. These were the larger public faces that dominate celebrity/political culture. For them he had no mercy. He had a “barge to nowhere” upon which he put these public personae he couldn’t countenance. Sometimes the barge was an ark and at other times a cement barge, ready to sink. Either way it always went nowhere. We didn’t always agree on his choices, but he loaded them on regularly. “Here is today’s passenger list – Andy Warhol, George Plimpton, Billy Martin, E T, Claus Von Bulow, Frank Sinatra. The barge departs for nowhere at 6:03 ¾ PM sharp.” The list got longer by the years, so long that he was regularly saying that he had to add another barge.

These were his nowhere people, the detritus thrown up by an entertainment celebrity culture that he felt was destroying the soul of the country. He was right.

When on a trip to Michigan, he saw a tee-shirt for sale, he wrote that “it would be perfect for you. It reads ‘Vote for Nobody’.” He knew his son. And when he wrote that “it’s a great big beautiful wonderful world, but half the people in it are nuts,” I couldn’t help laughing in recognition.

Voices bring presence. My father and I were together again through his letters.

“I hope you are keeping some sort of record,” Leonard Cohen intones in a song.

It’s good advice. Soon there may be for many no known father, no voice, no letters, no record, just some sperm deposited somewhere for someone. Nowhere fathers. I can hear my father saying, “You can bank on that.”

In one of his last letters to me he wrote, “I am hooked up to a heart monitor and have been examined by a neurosurgeon named Block. I think he is H.R. Block of tax forms. I have also just signed a consent form for a cat scan. I think that’s to see if I like cats.”

He died not long after. But before he did, he wrote, “Today is, or would have been, your uncle Vincent’s (his brother) birthday. I was thinking of inserting one of those in memoriam notices in the Daily News – you know, ‘Happy Birthday in Heaven Vince old boy,’ but I don’t think he’d see it.”

Quien sabe?

Thanks Ed my spirit was lifted.

Similar to Gary, when thinking of my father, I feel that I never asked the questions I could have asked. Even at the time he was declining physically and living in a nursing home, I was consumed by the responsibility to make decisions about his care and the care of my mother, who was still living at home, but increasingly suffering with dementia.

The value that talking to elder people can have cannot be overstated, especially in these days when we are very aware that “official” history is distorted in a number of ways. My youngest brother has been diligent in talking to our older relatives and putting together the family tree.

We are encouraged in our culture, what is left of it, to look to electronic media to learn what is going on. Of course, that is a trap. We need to take advantage of the people who have seen the world in the past, to open that book they hold in their head.

I have done that to some extent in reading books, but not enough with the personal resources available to me, and it is too late change that now.

As long as one’s father gives Love, that is enough.

Well Ed, I would tell you about my relationship with my father, but no one needs anymore nightmares !

I’d like to read more about your relationship with Mrs Grossman. Now that seems very interesting.

Listening to my father.

I too had a wonderful and intelligent father. He has been gone for 22 years though he has a positive influence on me every day. I am always asking myself, what would dad say?

This world would be a much better place if all had fathers such as ours.

Thanks for the memories.

I had a similar experience with a man who served as my father. Sitting on the porch the other morning, I began to remember one incident after another of when he tried to prepare me my future. My own father, who was a very good man in his own right, travelled extensively. Last week, I remembered when he told me, at age 6, that I should be looking for a man who liked smart women. Those kind of men were worth more. Thanks for sharing those priceless pearls.

Thanks for sharing your dad with us Ed. Its nice to see where you get some of your gifts.

I’m not one for regrets typically, but my own father’s death back in 1982, when I was only 30 years old, has left me with some. When I look back I find that I wish I had taken him fishing more often in his older age (he died at 73), and I wish I had been mature enough to muster up the courage to ask him more about his life. There is so much I’d like to know, that I can only try to piece together from others in the family, rather than my dad himself.

I do think my father’s death 40 years ago is connected to my decision to undertake the trip I just finished yesterday. I flew to the midwest, picked up my 22 year old grandson and we drove to the Upper Peninsula of Michigan to spend a week camping and fishing with one of my brothers and four of my nephews. I wanted my grandson to meet and get to know the men in my family who were all in various ways influenced by my father. And I wanted him to know that these older men, ranging from age 54 to 66 would all be there for him in the future when I’ve departed for that great trout stream in the sky (or where-ever).

In an era that seems bent on destroying all connection to the past, to history, to even “reality” itself – I reveled in the campfire stories shared, the family history shared, and the power of love, and of older men being willing to mentor younger men. My grandson experienced a right of passage, and I felt the sense of “passing on” connections between the generations of a love of the natural world and an honoring of all of our interconnections.

I wish our father’s could have met Ed – it would have been a hoot listening to their observations and commentary on our crazy world, no doubt.

Wonder Full recounting Ed. You are blessed beyond compare with the father you were given. Mine was a general surgeon and I am very lucky to have been given him. I learned worlds from him. However, there was not the ineffable level of communing between us as you were graced with.

Letters ARE coin-of-the-realm, tragically rejected and forgotten in the current final act of this nowhere people era. The electronic words reality of what I am currently punching in here leaves us all beggars and paupers. The entertaining-ourselves-to-death world of fleeting images has debased our visceral connection with each other to the eternal detriment of all who follow us here.

Although posted in your 2 Feb 2022 Nostalgic for the Future, it is relevant to again evoke Carl Jung’s appreciation in Memories, Dreams, Reflections of the vital necessity of understanding “what our fathers and forefathers sought”: